Waste Paper City

By P. J. Parsons (reproduced by permission of Omnibus; abridged by Gideon Nisbet, 1997).

Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.

The citizens of this county town, five days journey by road (ten by water) south of Memphis, called it Oxyrhynchus, or Oxyrhynchon polis, ‘City of the Sharp-nosed Fish’.

The fish was sacred: the Greek settlers after Alexander’s conquest adopted Egypt’s sacred animals alongside their own gods. The descendants of these settlers ran Egypt for a thousand years, right down to the Arab conquest. In their towns they spoke, wrote and read Greek; worshipped their fish and learned their Homer.

Sabina and her key

Even the ruins have perished. When Egyptologist Flinders Petrie went to Oxyrhynchus in 1922, he found remains of the colonnades and theatre. Now a single column meets the eye: everything else has gone, building material for modern houses.

The 'Pillar of Phocas', drawn by Baron Vivant Denon, 1798

Yet we know far more about Oxyrhynchus as a functioning town, and about its people as living individuals, than we do about many more glamorous ruins.

We know where Thonis the fisherman lived, and Aphynchis the embroiderer, and Anicetus the dyer, and Philammon the greengrocer. We know how much farmers had to pay when they brought in dates and olives and pumpkins to market. We know that on 2 November, AD 182, the slave Epaphroditus, eight years old, leaned out of a bedroom window to watch the castanet-players in the street below, and slipped and fell and was killed. We meet Juda, who fell off his horse and needs two nurses to turn him over; Sabina, who hit Syra with her key and put her in bed for four days (ancient keys are good solid objects); Apollonius and Sarapias, who send a thousand roses and four thousand narcissuses for the wedding of a friend’s son.

The reason we know so much, and in such detail, is rubbish.

Priceless rubbish

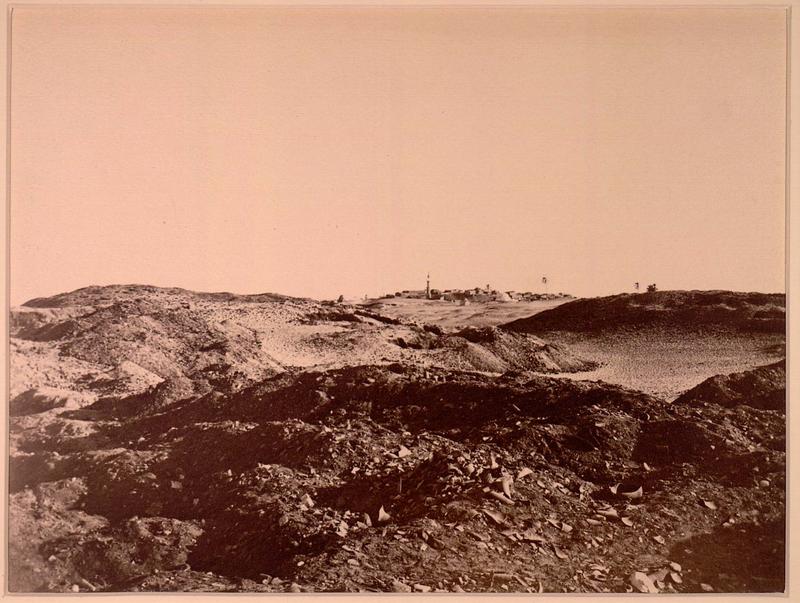

The town dumps of ancient Oxyrhynchus remained intact right up to the late nineteenth century. They didn’t look exciting, just a series of mounds covered with drifting sand. But they offered ideal conditions for preservation. In this part of Egypt it never rains; perishables which are above the reach of ground water will survive. In the dumps was something which the famous sites of classical Greece and Italy could not preserve: papyrus, the ancient equivalent of paper.

The Rubbish Mounds of Oxyrhynchus

Papyrus meant two things: documents and books. On both scores, these Greeks on the Egyptian fringe could fill blanks in the record.

Paper wraps stone?

The traditional classical world leaves us only the grand official documents it inscribed on stone. Oxyrhynchus yielded a huge random mass of everyday papers — private letters and shopping lists, tax returns and government circulars ... maybe 50,000 in all.

Excavators unearth scraps of papyrus

The traditional classical world leaves us no actual books: the great Library of Alexandria, the twenty-eight public libraries of imperial Rome have disappeared without trace. We are left with copies of copies, chance survivals through the Empire and Middle Ages. We have ideas of what’s missing, but these losses seemed final.

Sporadically and in fragments, the dumps of Oxyrhynchus are changing all that. Oxyrhynchus restores to us authors famous in classical times, who went under in the Middle Ages: the songs of Sappho, the sitcom of Menander, the elegant and learned elegies of Callimachus that Roman poets liked to boast of imitating. These Egyptian Greeks read Greek tragedies that to us had just been names — and the satyr plays that went with them.

Tony Harrison's Trackers of Oxyrhynchus at Delphi: modern play, ancient fragments

The diggers

It was only in the late nineteenth century that people began to realise what the dumps might offer. Egyptian peasants had made finds by chance, and sold them to western museums; scholars began to wonder what could be got by systematic excavation. And so it was in 1897 that the City of the Sharp-nosed Fish came back to life.

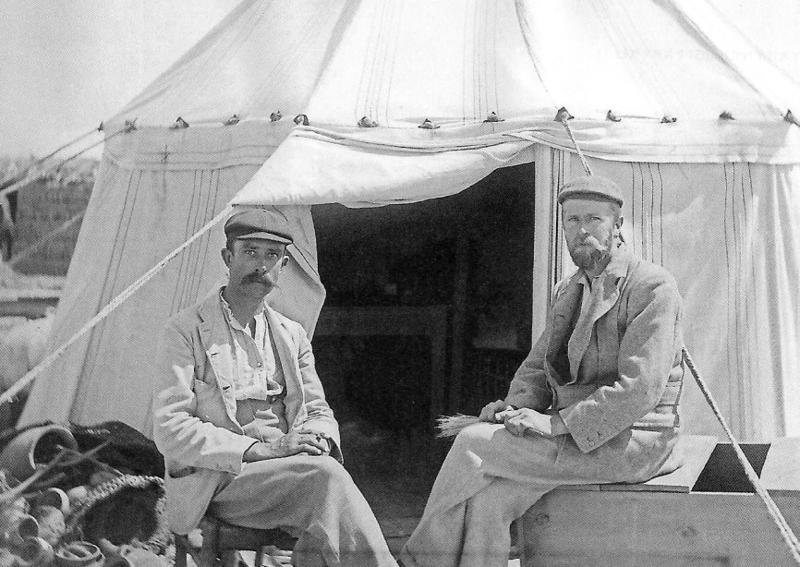

The excavators were two men in their late twenties, operating from Oxford and financed by the Egypt Exploration Society of London. Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt had become friends when scholarships took them to Queen’s College, Oxford (they were off mountaineering together in the Tyrol in the summer holidays of 1889). By 1895, now on graduate scholarships, they were in Egypt. They were to spend the rest of their lives pioneering a new branch of classics: papyrology.

Grenfell and Hunt in 1896

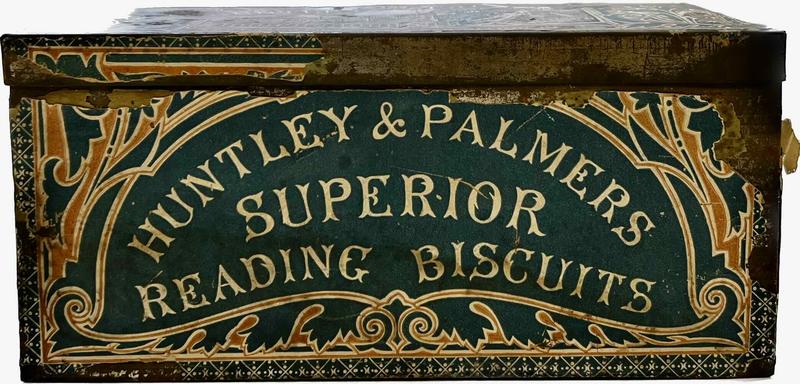

"Huntley and Palmer's Best"

Winters were spent in Egypt. Thirty foremen and a hundred workmen (in those days the wages came to £30 a week for the lot) attacked the mounds. They found papyri, mixed with earth and other rubbish, heaped thirty feet deep.

The finds were collected in baskets, then boxed and shipped back to Oxford - one roll in an old biscuit tin ("Huntley and Palmer's Best"). It was a lonely life, and even potentially dangerous; a shopping list of Hunt’s includes medicines, fish-hooks, The Old Curiosity Shop and a revolver with forty cartridges. “Good luck with the gravedigging”, wrote Grenfell’s brother.

Challenges and discoveries

Summers were spent in Oxford. Here there were more comforts (we find Grenfell ordering ‘500 Best Egyptian Cigarettes’ from a London dealer — the cost, in 1896, £1 7s 6d); but no less work. The papyri offered quite new problems: strange fragmentary poets, whom no one in the West had read for fifteen centuries; documents in late technical Greek from this unknown outpost of Hellenic civilisation.

Sixteen substantial volumes appeared, published jointly: each editor revised what the other wrote. It was an ideal partnership: Grenfell impetuous and extrovert, Hunt shy and cautious; one contributing ideas and intuitions, the other control and critical judgement.

It was not to end happily. In 1920 a third nervous breakdown ended Grenfell’s working life; Hunt went on until 1934, his last years clouded by the early death of his only son. But their partnership had achieved extraordinary things. They had brought back to life both the people of Oxyrhynchus and the books they read.